As an institution focused on fighting injustices, raising awareness about social inequities, and creating a fairer criminal justice system, one of our strongest tools for change is research data. That’s why, on September 23, the eve of our 2019 Smart on Crime Innovations Conference, four of our world-renowned research center directors, along with an inspiring alumnus, gathered together to discuss their experiences, their research, and their hopes for the future. The event, attended by faculty, staff, alumni, board members, public officials, and valued friends of the College, started off with mingling and networking on the Mirante Dining Terrace. Then, the researchers settled into their chairs in front of the audience, and their in-depth talk on criminal justice issues began.

“Data helps raise awareness, which can lead to changes in policies, laws, and lives.” —Karol V. Mason

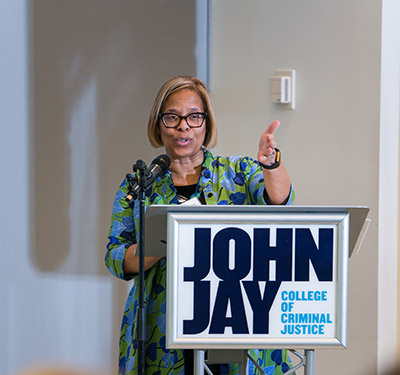

The President’s Message

President Karol V. Mason, first introduced the four directors: Jeff Butts, Ph.D., Director of the Research and Evaluation Center (JohnJayREC); Preeti Chauhan, Ph.D., Director of the Data Collaborative for Justice (DCJ); Ann Jacobs, Executive Director of the Prisoner Reentry Institute (PRI); and Lucy Lang, Executive Director of the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution (IIP). Then she explained why their work was so critical for advancing difficult criminal justice issues. “Data helps raise awareness, which can lead to changes in policies, laws, and lives,” said Mason. “The United States has the dubious distinction of locking up the highest percentage of a country’s population.” She went on to say our country makes up five percent of the world’s population, but we have 25 percent of the world’s prison population. And, that despite having the lowest crime rates our country has seen in decades, we have 2.2 million people behind prison bars. “Our four panelists are all committed to reimagining our criminal justice system to reflect the ideals in which our country was founded on—fairness and opportunity.”

The Message from Jeff Butts

Butts didn’t start his career as an academic or even a researcher. In the beginning of his career he was a social worker, working in the juvenile courts doing drug counseling for young people. “Back then, I assumed that those agencies—juvenile court, child welfare, and foster care—existed to pursue the goals that they announced were their goals. And then I learned that wasn’t the case, and that their first job was to protect themselves and their budgets. So, I went back to school and got a Ph.D.,” said Butts. After working in university settings and non-profit organizations, Butts realized that a specific type of research was his true passion. “I think the intersection of academics, scholarship, and applied research is the most exciting place to be,” said Butts. “John Jay is one of the few universities where that’s what we do all day long.” He went on to explain that “basic research” is done for knowledge purposes and to find out empirical facts about the world. But, “applied research”—his research of choice—is research done with an intent to make it useful for practice, policy, and decision makers.

“I think the intersection of academics, scholarship, and applied research is the most exciting place to be.” — Jeff Butts

Currently, Butt’s Center is working with the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice to evaluate the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP), an initiative designed to improve living conditions in public housing. “This is the biggest contract we’ve ever had,” said Butts. “We also work on violence prevention, and have been evaluating the Cure Violence model, which is where you hire people from communities affected by gun violence—people who were previously criminal justice-involved individuals and know that life—to try to get younger generations to see the future they want them to have, and not the one they are heading toward.”

“Our most recent report on marijuana enforcement and race disparities, was used by New York State legislators as a basis for decriminalizing marijuana possession enforcement.” — Preeti Chauhan

The Message from Preeti Chauhan

Early on in her career, Chauhan, a trained clinical psychologist, worked with girls and young women in detention centers before and after they were released. “One of the things that I noticed consistently was that all of these girls had very difficult backgrounds, abuse, and trauma. And, consistently when I was going out into their neighborhoods after they were released, I noticed that the girls of color were particularly disadvantaged,” said Chauhan. “It seemed like their reentry into the system was inevitable and I became really interested in understanding racial disparities and how to create a fairer justice system.” So, 10 years ago, when she got the opportunity to come to John Jay—a school that has a mission of social justice—she jumped at the chance.

“A few years after I came here, Jeremy Travis, who was the then-President of John Jay, had this idea. He told me that we should do something around misdemeanors because there was a lot of focus on felony crimes, and at the time in New York, there was a lot of focus on stop, question, and frisk,” said Chauhan. “We didn’t know much about misdemeanors and summons. Fortunately, through funding from the Arnold Foundation, we created a series of reports and data access, where we produced who’s coming in contact with the system for these lower level offenses, why they are coming into contact with it, how its changed over time, and what are the outcomes of these very high-volume activities.” Her research at the Center has had an impact on summonses and has been used to inform citywide legislation on the Criminal Justice Reform Act. “Our most recent report on marijuana enforcement and race disparities, was used by New York State legislators as a basis for decriminalizing marijuana possession enforcement,” said Chauhan. “Some of our successes early on helped us gain more funding to create The Research Network on Misdemeanor Justice.”

The Message from Ann Jacobs

In 1968 Jacobs was a student in the midst of the country’s biggest struggles—the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Women’s Movement. She didn’t know what she wanted to do, but she knew she wanted to help make the world a better place. “Luckily, I had a sociology professor who recognized my restlessness, and who encouraged me to do an internship at Project Crossroads—which was a Department of Labor funded initiative recognizing that people who got a criminal conviction were less likely to get employed,” said Jacobs. “There I was, a 19-year-old, white kid from the suburbs, who was placed in an office building, in an open room, filled with black men, all of whom had done time and were counseling youth on how to take a different path than the one they had taken. I got a chance to be an observer into a world that otherwise would not have been accessible to me. One thing led to another, and 50 years later, I’ve had a career in criminal justice reform.” For Jacobs, criminal justice and the impact of mass incarceration was the civil rights issue that would change the trajectory of her life and be her life’s work.

When Jacobs came to John Jay she was encouraged by then-President Travis to think about the ways in which a research center focused on reentry could be of service to students and faculty. It was an opportunity to create fellowships, internships, and long-term placement for students in community-based organizations. “With the support of the Pinkerton Foundation, the Tow Foundation, and the David Rockefeller Fund, we have a robust portfolio that place our students in professional development opportunities that they would not have had otherwise.” With Jacobs at the helm, PRI is committed to helping people live successfully in the community after justice involvement, and a significant portion of the Center’s work has been on increasing access to higher education for people who have been involved in the criminal justice system. “We get to do this through our college program at Otisville. We do it through credit-bearing classes at the city jail, all intended to develop a pathway for people to higher learning when they get out.”

“Inside Criminal Justice is going into its fourth semester, in our fourth prison. It’s changing hearts and minds in DA’s offices.” — Lucy Lang

The Message from Lucy Lang

Lang spent the bulk of her career, 12 years, in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office as a prosecutor. “About 10 years into my time there, I realized that the depth of my compassion towards victims and witnesses in cases had led to a kind of blindness with respect to the consequences of my decision making,” said Lang. “As a result, I piloted a college course in Queensboro Correctional Facility that brought together incarcerated students and prosecutors to study criminal justice together.” Lang described her transformation as a radical form of empathy that interestingly enough coincided with the birth of her children. She realized that she couldn’t look away from the impact of her work on different communities. “Which isn’t to say that I am not proud of the work that I have done as a prosecutor, because I am,” said Lang, “but I know that prosecutors like myself, can do it differently if decisions aren’t based on instinct.”

A year ago, Mason approached Lang with the position at the IIP, offering her the opportunity to build upon her legal skills and experiences, and her deep-rooted feelings of compassion. Since then, she’s brought her prosecutors class “Inside Criminal Justice” with her, and it has expanded to several additional District Attorney’s offices. “Inside Criminal Justice is going into its fourth semester, in our fourth prison. It’s changing hearts and minds in DA’s offices.”

“PRI is not about transforming systems through research and advocacy, it’s about transforming systems through individuals, by demonstrating what’s possible with those who’ve been negatively impacted.” —Ronald Day

The Message from Ronald Day

The evening’s most inspiring message came from John Jay alumnus Ronald Day, Ph.D. ’19. He perfectly illustrated how access to education can transform a person’s life. “Ronald grew up in the Bronx. He dropped out of high school in the ninth grade, and he made ends meet the only way he thought he could, by selling drugs. By a sheer twist of fate, Ronald earned his GED before he got involved in the criminal justice system,” said Mason, as she introduced Day to the crowd. “Having his GED enabled Ronald to immediately pursue a college education while he was incarcerated for 15 years. Upon his release, Ronald had 51 college credits. After coming home he earned his bachelor’s degree and his master’s degree. And, this past December he successfully defended his dissertation and received his doctorate degree from the CUNY Graduate Center/John Jay College.” Day is now the Vice President of Programs for The Fortune Society, helping to uplift and educate criminal justice-involved individuals.

“I just want to continue to be a part of the solution, and let the world know what’s possible when we allow people to earn an education.” —Ronald Day

Day went on to explain that he was sentenced to 15 to 45 years in prison, and that he started his “educational odyssey” in Sing Sing Correctional Facility. While there, he hoped to earn some college credits, potentially a college degree, and when released, positively impact his community. “But two years into the program, they snatched the rug out from my feet and other’s feet,” said Day. “It was hard and unfortunate because once you get involved in education you realize how much of a commitment it is, and how transformative it can be in your life. It was pretty sad to see it go, but I stayed positive, doing constructive things while I was inside. And, I made a full commitment to pursue education once I was released.” Before Day “came home,” he reached out to PRI. They told him that they could help connect him to different colleges and support him with his transition. “They honored that commitment to the fullest. They truly offered the support that a student transitioning from 15 years of incarceration needed,” said Day. He went on to say that he admired the work, advocacy, and research all of the centers were doing, but he noted a special difference he found with PRI’s model. “PRI is not about transforming systems through research and advocacy,” said Day. “It’s about transforming systems through individuals, by demonstrating what’s possible with those who’ve been negatively impacted. How many times do we have to do studies on the benefits of education for those that are incarcerated? How many more research studies do we need? Myself and all of the individuals in PRI are living examples of this work.”

Thinking of his own educational and career trajectory—finishing a bachelor’s degree, then a master’s degree, then another master’s degree in route to the Ph.D., and now being a Vice President at The Fortune Society—Day only had one moment of bittersweetness. He was proud that his mother witnessed all the positive changes he had accomplished in his life. She was even planning to wear three different dresses to his doctoral graduation celebration. But sadly, his mother passed away two years before his doctoral graduation. For Day, her pride in his community work is one of the driving forces that keeps him focused. “I started college in Sing Sing, now I’m back teaching in Sing Sing through Columbia University. I just want to continue to be a part of the solution, and let the world know what’s possible when we allow people to earn an education.”

More scenes from the event:

Videos